That the Arab Spring has come and gone and anti-American sentiment remains as explosive as ever throughout the Muslim world should surprise no one. After all, this is an instance of democracy materializing from thin air without the tradition or institutional convention that gives it substance. Post-Arab Spring democracy is a process without a corresponding culture, and as such, it doesn’t (and may never) connote any innate attachment to Western values such as freedom of speech or the rule of law.

More important from an analytical point of view is the power shift that has taken place in the domestic politics of Arab Spring countries. Groups that formerly operated on the fringe of national politics have now ascended to the highest levels of power. The actual ideology of the new dominant parties isn’t fundamentally important, whether it’s the ostensible liberalism of the National Forces Alliance in Libya or the presumably more hardline Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. What matters most is this: all of them are competing for political power and the rules of the game haven’t quite crystallized yet.

If the hallmark of a highly developed democracy is its ability to protect minorities from the tyranny of the majority, can anyone reasonably expect that the populist pay dirt of anti-Americanism won’t be brandished in institutionally immature Arab Spring democracies?

Now enter the ‘Innocence of Muslims’ debacle that has killed four US diplomats, produced massive protests throughout the Muslim world, and most recently engendered a pullout of non-essential US diplomatic personnel from Sudan and Tunisia. This is the first big test for not just post-Arab Spring governments in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia, but for US foreign policy as well.

However, US policy options are limited by the proliferation of the very ideology it champions. Washington can no longer lean on autocrats like former Egyptian President Mubarak to reign in public displays of anger towards Israel and the West, and it remains to be seen whether these same populist sentiments will eventually make their way into Egyptian policy as well.

Now that the direct autocratic channel is a thing of the past, the US government can only engage in a kind of pseudo public relations (PR) campaign aimed not just at ending the protests and removing their direct threat to American citizens and property, but also allowing the Egyptian authorities to save face in the eyes of their own public and thus insulate future US-Egyptian relations as well. Obviously, the US government can’t monitor every offensive video that appears on YouTube. But Washington, and presumably every other government involved, already knows this, so the only viable PR option is to offer up a few symbolic gestures and hope that the protests will lose momentum and fizzle out. Constant high-level public apologies and condemnations of the video, contacting YouTube about its removal, and bringing in the film’s producer for a probation-related ‘interview’ are presumably all symbolic gestures aimed at defusing the crisis; they are meant to communicate a message directly with populations that haven’t been politically relevant in the foreign policy sense for decades.

Libya is the inverse of Egypt insofar that the total lack of influence during the Gaddafi era was supposed to contrast starkly with the expected renaissance of US-Libyan relations after he was removed, thanks in large part to US military assistance. But the attack in Libya is different from Egypt, Yemen, and Tunisia. It is not as indicative of widespread anti-American sentiments and extremism as it is elsewhere. Rather, it suggests overarching lawlessness and a security vacuum throughout the country. This was Benghazi after all, the birthplace of the Libyan revolution and an area that was presumed safe enough for the US ambassador to operate without an armed guard. There may be some truth in Libyan President al-Magarief’s suggestion that the attacks were planned well ahead and thus not even connected to the ‘Innocence of Muslims’ video.

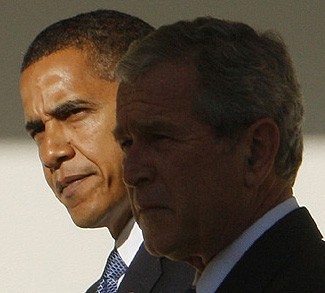

Last week, President Obama stunned some observers when he referred to Egypt as ‘not an ally, but not an enemy.’ This rhetorical re-classification of a former stalwart of US foreign policy in the region caused such a stir that the White House had to issue a subsequent statement re-iterating the two countries longstanding relationship. Yet the frankness of the original statement hints at what form short term US foreign policy towards Arab Spring countries is likely to take: ‘wait and see.’

Until the full fallout from the Arab Spring is known, Washington will continue to walk a fine foreign policy line; one based on symbolic PR gestures and a ‘wait and see’ approach. There is no question that the Arab Spring has damaged America’s capacity for a realpolitik foreign policy in the region. It’s just a question of how badly.