This time last year, the majority of financial commentators held a downbeat outlook for the global economy in 2013. The potential for instability was seemingly high, but in reality it turned out that the greatest shock was a lack of any major shocks.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve reduced its monetary stimulus measures and stock markets actually rallied on the news. Unemployment fell to a five-year low of 7% and a government shutdown came and went without hysteria. An unfamiliar calm reigned over the eurozone through the year, resulting in a welcome decline in bond yields for the weaker “periphery” nations. China successfully reversed its slowing growth, while Japan’s extraordinary stimulus policies helped reinvigorate an economy that has suffered a quarter century of stagnation.

By year end there was synchronized growth from the major global economies, pointing to an optimistic outlook for 2014. The smooth navigation through so many potential shocks naturally bodes well for this year, but enough headwinds remain to keep growth modest.

US Growth Gaining Momentum

Expectations are relatively high for the US economy, with growth forecasts broadly surpassing the expected final 2013 figure of 2%. The economic drag caused by the sequestration budget cuts will no longer be a factor and significant progress has been made in reducing corporate and household debt. Moreover, developments in shale energy will aid US manufacturing, particularly in the petrochemical sector. A stable environment should bring near-term benefits to rising asset prices and the housing market.

Yet several issues cloud the positive outlook. The Federal Reserve may have begun tapering its quantitative easing strategy without market panic, but the timeline of its ultimate exit from the stimulus program remains unclear. And while there are signs that political gridlock in Congress may abate somewhat, it is unlikely that there will be any development of progressive fiscal policies. Moreover, household income levels are expected to remain stagnant, meaning that a robust increase in consumer spending is unlikely, casting doubt on whether the US economy can make a smooth transition from central bank stimulus to self-sustained growth.

Japan’s Stimulus Measures Fruitful, For Now

The aggressive monetary expansion launched by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in late 2012 has delivered on its intention to reverse deflation. The rationale behind the initiative is that sustained inflation will see depressed wages rise and boost consumer spending as households realize that prices will no longer follow a downward trajectory. Growth and inflation both rose last year and 2014 should see a continued increase.

A potential risk to growth exists in the introduction of a 3% sales tax increase which may dampen economic activity. Abe has promised further stimulus to offset any negative impact from the tax; a strategy which should prove successful. But the need for the rise in sales tax is a more serious issue. Japan must ease its huge public debt burden, which is forecast to reach 230% of GDP in 2014. Financing such debt can be treacherous, and a sharp rise in Japan’s sovereign bond yields would make debt-servicing costs unsustainable. Such an outcome would prove disastrous for the Japanese economy.

Eurozone: The New Japan?

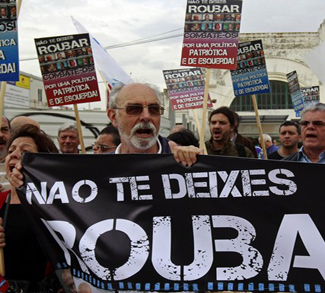

While Japan recovers from decades of deflation, the eurozone risks falling into its own trap in 2014. 2013 was good for the eurozone largely because nothing much happened; financial markets interpreted no news as good news. Fears of a breakup have cooled and the 17-country bloc emerged from recession last year. But growth in 2014 is expected to be minimal, inflation is anemic and major structural issues remain.

Eurozone unemployment remains stubbornly high at 12.1%, with several of the bigger nations hampered by a lack of competitiveness due to high labor costs and a strong currency. The leadership may be moving away from the ideology of severe austerity measures, but public debt levels remain elevated and nations will need to continue to improve their financial balances to attract foreign investors. Similarly, banks will remain in deleveraging mode, especially following region-wide stress tests, resulting in a continuation of tight credit conditions.

Some support should come from the ECB through easier monetary policy, aiding market sentiment over the near-term. But progress on a banking union shows signs of remaining painfully slow and developments on fiscal union are nonexistent.

Economic and Debt Growth in China

Ballooning debt growth in China has been a burgeoning issue over the last couple of years. In 2012, China’s central bank made efforts to tighten credit, but these initiatives slowed economic growth. That was an undesirable outcome for the leadership, so last year credit conditions were eased and infrastructure investment was increased. Chinese economic growth rebounded quickly, calming fears of a “hard landing.”

Creating more debt will not help China in the long-term. Beijing is attempting to change its model from a reliance on foreign demand for its exports to an economy driven by sustainable domestic consumption. But households do not have adequate wealth to drive the economy, and have therefore relied on debt to maintain growth. The Chinese leadership will need to introduce significant economic and political reforms to reduce its reliance on debt. However, during the transition it must be careful to maintain growth and avoid any crash that would have a far-reaching impact.

Conclusion

2013 turned out to be a pleasant surprise for global markets, spurring optimistic forecasts for the year ahead. 2014 will likely be a better year for global growth and many near-term risks have dissipated. Yet such upbeat sentiment should not distract from the political dysfunction and absence of progressive reform policies in some of the world’s most significant economies.