Op-Ed

Every day, the critical December summit in Copenhagen grows closer. All agree that climate change is an existential threat to humankind. Yet agreement on what to do still eludes us.

How can this be? The issues are complex, affecting everything from national economies to individual lifestyles. They involve political trade-offs and commitments of resources no leader can undertake lightly. We could see all that at recent climate negotiations in Bangkok. Where we needed progress, we saw gridlock.

Yet the elements of a deal are on the table. All we require to put them in place is political will. We need to step back from narrow national interest and engage in frank and constructive discussion in a spirit of global common cause.

In this, we can be optimistic. Meeting in London earlier this week, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown told the leaders of 17 major economies (responsible for some 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions) that success in Copenhagen is within reach—if they themselves engage, and especially if they themselves go to Copenhagen to push an agenda for change.

U.S. leadership is crucial. That is why I am encouraged by the spirit of compromise shown in the bipartisan initiative announced last week by John Kerry and Lindsey Graham. Here was a pair of U.S. senators — one Republican, the other Democratic — coming together to bridge their parties’ differences to address climate change in a spirit of genuine give-and-take.

We cannot afford another period where the United States stands on the sidelines. An engaged United States can lead the world to seal a deal to combat climate change in Copenhagen. An indecisive or insufficiently engaged United States will cause unnecessary — and ultimately unaffordable — delay in concrete strategies and policies to beat this looming challenge.

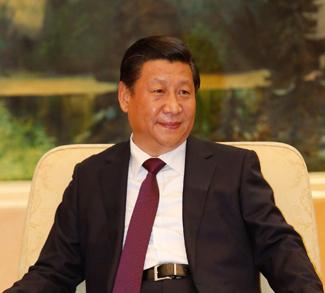

Leaders across the globe are increasingly showing the engagement and leadership we need. Last month, President Barack Obama joined more than 100 others at a climate change summit at U.N. headquarters in New York — sending a clear message of solidarity and commitment. So did the leaders of China, Japan and South Korea, all of whom pledged to promote the development of clean energy technologies and ensure that Copenhagen is a success.

Japan’s prime minister promised a 25 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2020, laying down a marker for other industrialized nations. The European Union, too, has pledged to make a 30 percent reduction as part of a global agreement. Norway has announced its readiness for a 40 percent cut in emissions. Brazil has unveiled plans to substantially cut emissions from deforestation. India and China are implanting programs to curb emissions as well.

Looking forward to Copenhagen, I have four benchmarks for success:

Every country must do its utmost to reduce emissions from all major sources, including from deforestation and emissions from shipping and aviation. Developed countries must strengthen their mid-term mitigation targets, which are currently nowhere close to the cuts that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says are needed. Developing countries must slow the rise in their emissions and accelerate green growth as part of their strategies to reduce poverty.

A successful deal must strengthen the world’s ability to cope with an already changing climate. In particular, it must provide comprehensive support to those who bear the heaviest climate impacts. Support for adaptation is not only an ethical imperative; it is a smart investment in a more stable, secure world.

A deal needs to be backed by money and the means to deliver it. Developing countries need funding and technology so they can move more quickly toward green growth. The solutions we discuss cannot be realized without substantial additional financing, including through carbon markets and private investment.

A deal must include an equitable global governance structure. All countries must have a voice in how resources are deployed and managed. That is how trust will be built.

Can we seal a comprehensive, equitable and ambitious deal in Copenhagen that will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global temperature rise to a scientifically safe level? Can we catalyze clean energy growth? Can we help to protect the most vulnerable nations from the effects of climate change? Can we expect the United States to play a leading role?

The best answer to all these questions was given last week by Senators Kerry and Graham: “Yes, we can.”

Ban Ki-moon is secretary general of the United Nations.